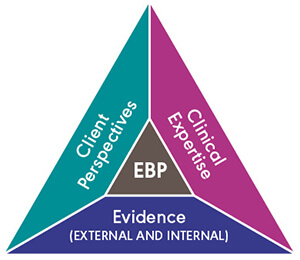

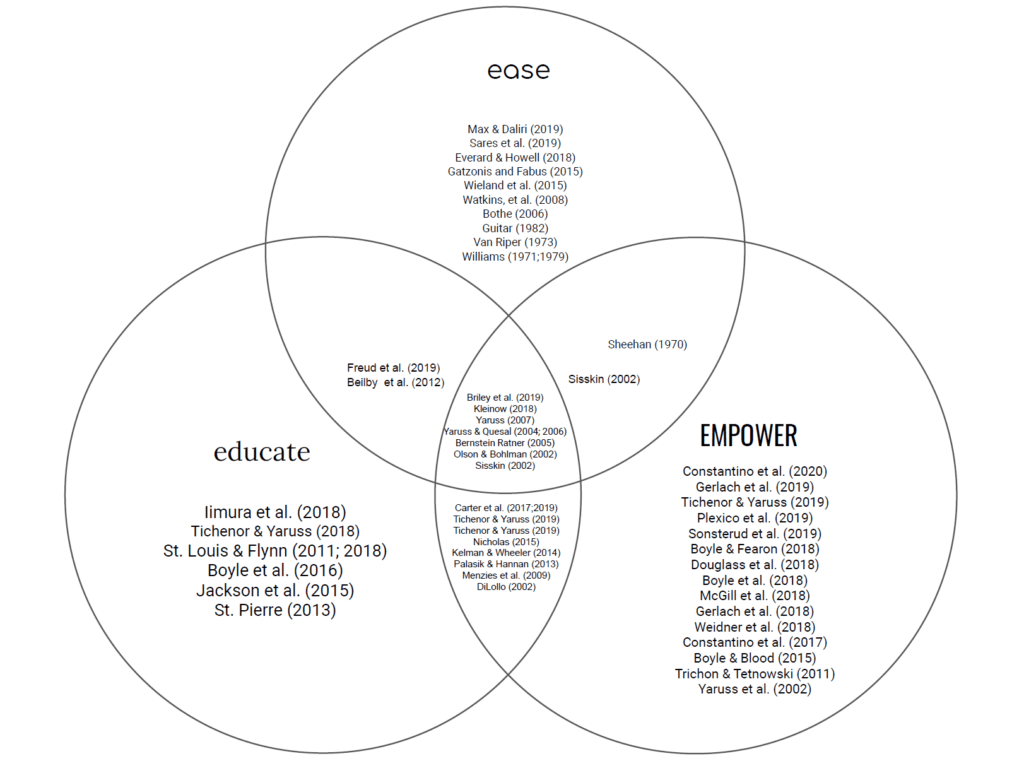

We at speech IRL were proud to unveil our 3Es model in a recent post as our overarching “approach” to speech therapy. With the knowledge that each client has a unique and nuanced set of needs, the process of identifying goals and planning treatments had always eluded a uniform step-by-step formula—until now. The 3Es supramodel (Education, Ease, and Empowerment) is broad enough to encompass all other therapy approaches, yet practical enough to help clinicians and their clients identify values-based goals and then plan specific treatments to reach those goals. A successful application of the model will create an accessible, robust, and structured “menu” of activities that can be flexibly combined throughout the course of treatment.

The need for a new supramodel became abundantly clear when we took a close look at research trends and developments from the last decade and noticed that most of it was not accounted for in a current therapy model. In this post we will provide some background information on the models that informed the 3Es, then take a dive into the research trends that we believe the 3Es model accounts for in ways that other treatment approaches have been insufficient.

If you love stuttering research, join us on July 14th for our next Dine & Development, where Courtney Luckman and Natalie Belling will summarize the latest and greatest in our trademark informal, conversational learning format. Eligible for ASHA CEUs!

Where did this model come from?

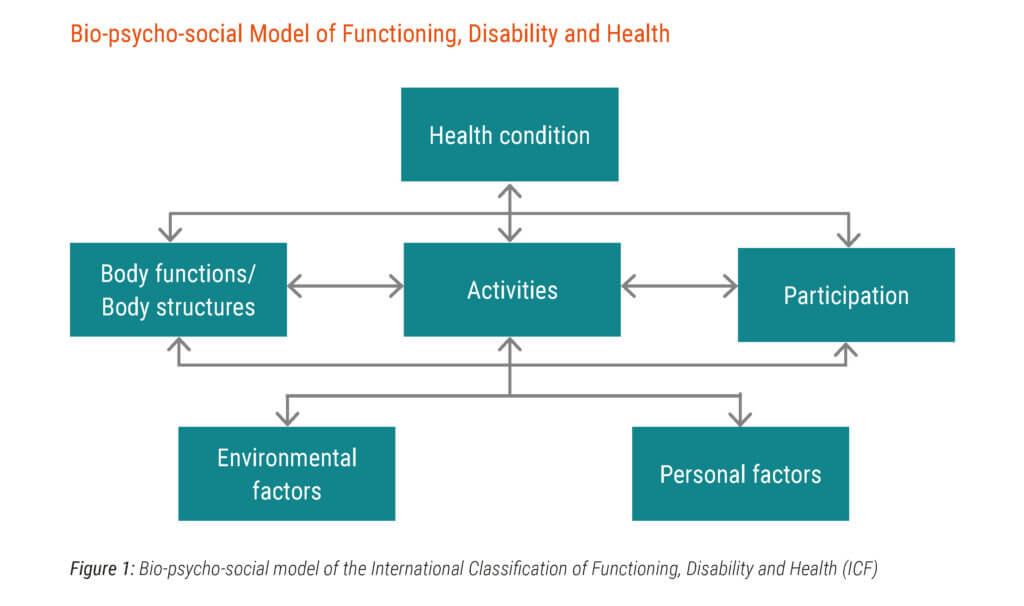

WHO-ICF model of disability.

Source: https://www.icf-casestudies.org/introduction/introduction-to-the-icf

The emerging trends that have challenged these existing approaches and others include re-defining the stuttering experience, defining covert stuttering, understanding the stigma of stuttering, anticipation of the stuttering moment, disability rights, and self-help and support. Additionally, recent research has supported the successful application of psychotherapy approaches in working with people who stutter.

Despite the rigid sense of defined, linear, and prescriptive approaches taught in communication therapy education, we know that real-life communication (speech In Real Life, if you will) is the total opposite: it is nuanced, dynamic, and contextual. And deeply, deeply personal. Read this post to learn more about using Education, Ease, and Empowerment to bridge gaps between theory and therapy in your practice, and check out our research dive below:

Research trend #1: Redefining stuttering

Efforts to define stuttering often come from the listener’s experience of stuttering. Researchers at Michigan State University are working to redefine stuttering from the perspective of the person who stutters. They describe24:

“The term stuttering signifies a constellation of experiences beyond the observable speech disfluency behaviors that are typically defined as stuttering by listeners. Participants reported that the moment of stuttering often begins with a sensation of anticipation, feeling stuck, or losing control. This sensation may lead speakers to react in various ways, including affective, behavioral, and cognitive reactions that can become deeply ingrained as people deal with difficulties in saying what they want to say. These reactions can be associated with adverse impact on people’s lives. This interrelated chain of events can be exacerbated by outside environmental factors, such as the reactions of listeners.”

“Taken together, the model shows that ‘stuttering is more than just stuttering’, meaning that the experience of the stuttering disorder, as lived by people who stutter, involves more than just observable disruptions in speech, as perceived by listeners.”

Research trend #2: Stigma

Some definitions:

Public stigma: what society believes about and how they act toward a stigmatized group; this includes stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination

Self-stigma: the individual applies the stigma to himself/herself or others with the condition

Enacted stigma: actual episodes of negative reactions and discrimination from the public that the stigmatized individual encounters

Felt stigma: shame associated with the stigmatized trait and the fear of being evaluated negatively by other people

Almost half of all people who stutter feel the need to hide the fact that they stutter2. This desire to conceal may result from a high amount of felt stigma (shame, fear) even with low levels of enacted stigma (actual negative experiences)4. This stigma can then lead to increased stress and decreased physical health1.

Speech-language pathologists can help clients understand their life events in a more empowering way, through self efficacy, to instill a sense of power and control1. One way to do this is through self-disclosure, or telling other people that you stutter. During the assessment process, clinicians can gather information about the client's openness and willingness to disclose2. During treatment, the clinician and client can work together to create functional self-disclosure statements.

Research trend #3: Anticipation

Anticipation, in regards to stuttering, is the cognitive or proprioceptive sense that one is about to stutter. There is a high prevalence of anticipation among people who stutter8. In response to this anticipation, a person who stutters may implement an avoidance strategy (changing words, changing topics, avoiding situations, look away, remain silent, etc.) or a self-management strategy (easy onsets, changing rate, breathe, etc.). Anticipation often leads to anxiety and uncertainty amongst people who stutter.

Clinicians are encouraged to take anticipation into account during assessment and treatment to help the client identify non-helpful anticipatory behaviors7,8. Researchers also recommend clients desensitize (reduce their fear) of anticipation through voluntary stuttering, use of eye contact, and stuttering modification techniques8.

Research trend #4: Support

As clinicians who specialize in stuttering, we’ve always emphasized the importance of self-help and support groups for clients who stutter. Only recently, however, has research begun to confirm this. Support groups (safe spaces for people who stutter to meet others who stutter) have positive benefits for both children and adults who stutter9,10.

When young people who stutter attend a stuttering support group they9:

- Have less negative reactions to stuttering

- Are more confident

- Are more likely to say exactly what they want to say

- Normalize stuttering

- Increase self-acceptance

- Build a sense of community

When adults who stutter attend a stuttering support group they:10

- Are less likely to avoid speaking situations

- Are more likely to talk about stuttering

- Are more likely to have successful speech therapy

- Report that stuttering interferes less with work and school

- Report communicating more easily

Research trend #5: Disability Rights

In a fairly recent movement in the stuttering community, advocates for disability rights for people who stutter state that the perception of stuttering as “broken speech” is constructed by both the speaker and the hearer12. A common example of disability rights is providing a ramp for a person in a wheelchair to help them access society. It is the environment that has to change, not the person. Proponents of disability rights argue that unclear and conflicting expectations are forced upon people who stutter, which causes stuttering to be seen as a moral failure12. It is important for people who stutter to understand stuttering through a disability rights lense. This will help them learn and develop self-advocacy skills. Adults who stutter should be aware of their right to a reasonable accommodation under the law, as stuttering is associated with disadvantages in the labor market; people who stutter earn less than people who do not stutter11.

Research trend #6: Covert Stuttering

Covert stuttering is a type of stuttering that exists when a person attempts to hide his/her stutter in order to pass as fluent. This “active form of resistance” occurs when a person who stutters learns that stuttering has ethical ramifications15. A variety of strategies are used by people who stutter to conceal their stuttering including avoiding stuttering, avoiding taking on the identity of a person who stutters, changing words, content, or sounds, and changing vocal tone15. People may become covert in an attempt to “shed the stigma of disability” and ‘become normal” in order to be perceived in the world as “professional.” Covert people who stutter are often managing high anxiety and significant cognitive impacts, especially when transitioning to more overt stuttering13.

Constantino15 notes:

“Up until the moment she stutters she is put in the “normal” category; however, the moment she stutters she is put in another category, she becomes disabled. It is not the presence or absence of her stuttering that disables her but her listener’s awareness of it. If she stutters and her listener does not notice, she is not disabled…The act of stuttering produces an ontological break, through which the participant falls into a different category of person.”

Researchers suggest the following activities for treating covert stuttering:

- Guide clients through saying feared words and entering situations where stuttering is likely15

- Practicing voluntary stuttering15

- Encourage comfort and acceptance of stuttering15

- Provide counseling13

- Provide clients with education about stuttering13

- Establish therapy goals collaboratively13

- Teach self-disclosure of stuttering14

- Encourage attendance in support groups13

Research trend #7: Psychotherapy approaches for stuttering

We’re getting to the end of our post, but I wanted to point out one last research trend: the importance of implementing psychotherapy approaches in stuttering therapy. Regardless of specific approach, rapport matters—a lot18. A positive working alliance in stuttering therapy is associated with positive outcomes 6 months post therapy, the most important factors being mutual agreement on therapy tasks and goals and client motivation.

Two approaches have been found to be successful in helping clients who stutter:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can help clients who stutter20,21:

- Decrease anxiety

- Decrease social avoidance

- Increase engagement in speaking situations

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) can help clients who stutter19:

- Observe themselves in the present moment

- Accept their thoughts

- Become more psychologically flexible

- Make values-based choices for future behaviors

In their own distinct ways, each of the above research trends falls through the cracks or breaks the boundaries of previous scholarship. We believe the lens of the 3Es will help clients and speech therapists understand what’s possible in a larger context that transcends limitations the field has come to accept because we didn’t have a big enough model. We offer this framework as a means to view all of our theories and treatments side by side and compare their efficacy in terms of Education, Ease, and Empowerment for the speech therapy client.

We’d love to hear what you think! Share your comments and stories with us by filling out our survey form.

References/for more information

- Boyle, M. P., & Fearon, A. N. (2018). Self-stigma and its associations with stress, physical health, and health care satisfaction in adults who stutter. Journal of fluency disorders, 56, 112-121.

- Boyle, M. P., Milewski, K. M., & Beita-Ell, C. (2018). Disclosure of stuttering and quality of life in people who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 58, 1-10.

- Boyle, M. P., Dioguardi, L., & Pate, J. E. (2016). A comparison of three strategies for reducing the public stigma associated with stuttering. Journal of fluency disorders, 50, 44-58.

- Boyle, M., & Blood, G. W. (2015). Stigma and stuttering: Conceptualizations, applications, and coping. In Stuttering meets stereotype, stigma, and discrimination: An overview of attitude research (pp. 43-70). West Virginia University Press.

- Flynn, T. W., & St. Louis, K. O. (2011). Changing adolescent attitudes toward stuttering. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 36(2), 110-121.

- Flynn, T. W., & St. Louis, K. O. (2018). Maintenance of improved attitudes toward stuttering. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology, 27(2), 721-736.

- Jackson, E. S., Rodgers, N.H., & Rodgers, D.B. (2019). An exploratory factor analysis of action responses to stuttering anticipation. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 60, 1-10.

- Jackson, E. S., Yaruss, J. S., Quesal, R. W., Terranova, V., & Whalen, D. H. (2015). Responses of adults who stutter to the anticipation of stuttering. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 45, 38-51.

- Gerlach, H., Hollister, J., Caggiano, L., & Zebrowski, P.M. (2019). The utility of stuttering support organization conventions for young people who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 62, 1-12.

- Trichon, M. & Tetnowski, J. (2011). Self-help conferences for people who stutter: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 36(4), 290-295.

- Gerlach, H., Totty, E., Subramanian, A., & Zebrowski, P. (2018). Stuttering and labor market outcomes in the United States. Journal of Speech Language Hearing Research, 61(7), 1649-1663.

- Pierre, J. S. (2013). The construction of the disabled speaker: locating stuttering in disability studies. In Literature, Speech Disorders, and Disability (pp. 17-31). Routledge.

- Douglass, J. E., Schwab, M., & Alvarado, J. (2018). Covert stuttering: Investigation of the paradigm shift from covertly stuttering to overtly stuttering. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology, 27(3S), 1235-1243.

- McGill, M., Siegal, J. Nguyen, D., & Rodriguez, S. (2018). Self-report of disclosure statements for stuttering. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 58, 22-34.

- Constantino, C. D., Manning, W. H., & Nordstrom, S. N. (2017). Rethinking covert stuttering. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 53, 26-40.

- Beilby, J. M., Byrnes, M. L., & Yaruss, J. S. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy for adults who stutter: Psychosocial adjustment and speech fluency. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 37(4), 289-299.

- Freud D., Levy-Kardash O., & Glick I, Ezrati-Vinacour R. (2019). Pilot Program Combining Acceptance and Commitment Therapy with Stuttering Modification Therapy for Adults who Stutter: A Case Report. Folia Phoniatrica Logopaedica.

- Sønsterud, H. , Kirmess, M. , Howells, K. , Ward, D. , Feragen, K. B. and Halvorsen, M. S. (2019), The working alliance in stuttering treatment: a neglected variable?. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 54: 606-619.

- Palasik, S. & Hannan, J. (2013). The clinical applications of acceptance and commitment therapy with clients who stutter. Perspectives of Fluency and Fluency Disorders, 23(2), 54-69.

- Menzies, R. G., Onslow, M., Packman, A.,& O’Brian, S. (2009). Cognitive behavior therapy for adults who stutter: A tutorial for speech-language pathologists. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 34, 187-200.

- Kelman, E. & Wheeler, S. (2014). Cognitive behaviour therapy with children who stutter. 10th Oxford Dysfluency Conference, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- Nicholas, A. (2015). Solution focused brief therapy with children who stutter. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 193, 209-216

- Constantino, C. D., Eichorn, N., Buder, E. H., Beck, J. G., Manning, W. H. (2020). The speaker’s experience of stuttering: Measuring spontaneity. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 63(4), 983-1001.

- Tichenor, S., & Yaruss, J. S. (2018). A Phenomenological Analysis of the Experience of Stuttering. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology, 27(3S), 1180-1194.

- Tichenor, S. E. & Yaruss, J. S. (2019). Group experiences and individual differences in stuttering. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62, 4335-4350.

- Tichenor, S. E. & Yaruss, J. S. (2019). Stuttering as defined by adults who stutter. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62, 4536-4369.

- Plexico, L. W., Erath, S., Shores, H., & Burrus, E. (2019). Self-acceptance, resilience, coping and satisfaction of life in people who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 59, 52-63.