Some months ago I had a phone call with a mother who was concerned about her child's ongoing stuttering. The story was a familiar one: began stuttering during the preschool years, attended therapy early on, speech improved. Now, a few years later, the stuttering had recently resurged, despite continued therapy.

She shared with me that she had spoken to another mother of a child who stutters, someone she met through a support network. "This other mom told me that stuttering is progressive, and it really scared me. That means it's just going to get worse! I don't know what to do."

We had a long talk, but this experience of hers stuck with me. Stuttering is not, in fact, "progressive", but it's a term that is often thrown around and very understandably confused with another technical p-word that the "experts" use: persistent.

What's the difference, and why does it matter so much? Well, read on...

Progressive

I will start with the meaning of progressive, for two reasons. One, it's pretty straightforward. Two, this is the thing that stuttering is not, and I feel it's easier to say what stuttering is not than what stuttering is.

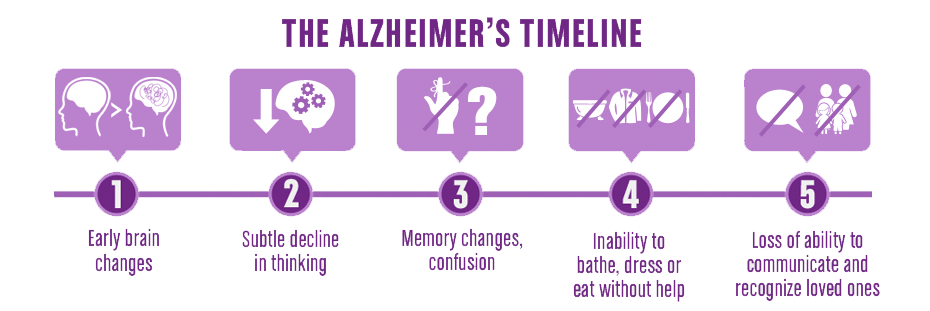

"Progressive", in the medical field, typically refers to disease processes that continually worsen over time once the diagnosis has been made. The disease "progresses" until the patient reaches a very final end, such as total loss of function of a specific function (eg, blindness) or the entire system (death). Diseases such as Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and ALS are progressive. The course may be very prolonged, as is often the case with dementia; or it may be devastatingly fast, such as in ALS.

Alzheimer's Treatment from http://www.alzheimerstreatment.link/dementia-stages-timeline-2/

The underlying neurophysiological nature of stuttering is not degenerative, and stuttering is not progressive. We know that stuttering is neurodevelopmental, resulting from differences in brain anatomy and function at an early age. Different does not equal degenerative (in the same way that autism is different, not degenerative).

This is extremely important to recognize, since it entirely changes the fate of people who stutter (especially young children whose parents worry about the future). If stuttering was truly degenerative, that would mean a child would get progressively more disfluent until, I suppose, s/he became utterly unable to communicate verbally at all (total loss of specific function). This would be very alarming for parents of young children who begin stuttering quite severely at a young age. At this rate, your child could be rendered mute by sixth grade!

Fortunately, of course, stuttering is not progressive, and I hope it's abundantly clear why we should take great care to not misapply this term. What is this term "persistent", though?

Persistent

It's difficult to fully explain this term without explaining some basic fundamentals about early childhood and stuttering, so hang in there for a moment.

It is considered normal for young kids, often categorized as ages 2-5, to go through a period of "developmental disfluency". They are stuttering, to the untrained eye. Kids who go through developmental disfluency usually grow out of it as naturally as they grew into it, with no speech therapy required.

However, for kids with true "childhood onset fluency disorder" (neurodevelopmental differences specific to motor speech production), the stuttering does not naturally go away. Speech therapy is strongly recommended for these kids.

Developmental disfluency and childhood onset fluency disorder (stuttering) can look very similar, even to speech-language pathologists sometimes. This is why it is considered "normal" for young kids to "stutter", even though most of them probably aren't actually "stuttering": they're getting lumped into the same bucket. It has been established that around 80-90% of children who exhibit stuttering-like disfluencies in their speech will recover. The other 10-20% continue to stutter. They persist.

I don't know who first coined this term, but basically, we use the word "persist" to mean "doesn't go away on its own". When an SLP evaluates a child for stuttering, one of the goals is to determine if the child is likely to recover on their own, or if they will persist. We have research and data about risk factors for persistence: for example, a child with a genetic family history of stuttering is at much greater risk for persistent stuttering.

Diving a little deeper

OK, so persistent basically means "isn't going away". It tells you what is NOT likely to happen. However, that doesn't tell you a lot about what IS likely to happen! (Which, I should like to note, is quite different from progressive, which tells you in no uncertain terms what is extremely likely if not definitely going to happen.)

This big question mark forecast is actually what makes persistent a very appropriate term for childhood stuttering, because if there is one predictable feature of stuttering, it's that stuttering is unpredictable. Quite frankly, we don't know what will happen long-term with a child's speech.

Stuttering can fluctuate, evolve, disappear, reappear, and completely reinvent itself over the course of a child's development (and even into the adult years). It may completely subside for literally years, only to suddenly reemerge with a never-before-seen vengeance. It may fluctuate, then stabilize for many years, only to take on a mind of its own again at the age of 19.

What we are learning more and more from neuroimaging studies is that regardless of the surface fluency or disfluency they exhibit, people who stutter have fundamental differences in how their brains produce speech. Sometimes this difference manifests as a disfluency, sometimes not.

I once had a client who summarized his feelings about the nature of his speech quite succinctly. He said, "I may not always stutter, but I will probably always have the propensity to stutter." It doesn't mean it will happen, it just means that it could happen. In fact, it means it also could never happen!

The next chapter

We seem to have ended on a depressing note. Persistent may not seem much more encouraging than progressive. Okay, so it's not a for-certain communication death sentence, but basically it means it's never going away?

Two brief answers. One, there are many, many anecdotal tales of adults who had persistent stuttering and self-report that they fully recovered at some point in their adult lives (30s, 40s, 50s). Neuroimaging research on this crowd has been slim, to my knowledge, so not much is understood about this process.

Two, I say this regarding the scary question mark that is the future of a child or young person with persistent stuttering. Your future is unknown. It may be rough at times, and we might even expect that you have a high likelihood of hitting some speech struggles.

But, what we do know about persistent stuttering is that nothing is set in stone when it comes to speech. So, there's not reason not to grab your own chisel and decide for yourself!

Don't ask fate, or science, ask yourself: what is your speech going to be like?

(That answer will have to wait for another post.) 🙂