Answers to those hard questions that you are too scared to ask.

“Can I ask you something?” my friend asked timidly.

“Sure,” I said.

What is happening when you are stuttering? Do you know what you want to say? What should I do when this happens?” my friend anxiously asked.

With her voice cracking and her eyes diverting from mine, I could tell that these were hard questions for my friend to ask. I smiled, and thanked her for asking. These were really good questions.

I find that society has come a long way in its interpretation and acceptance of stuttering, but subtle (well-intentioned) assumptions still remain. As a person who stutters and speech-language pathologist, I am frequently asked the following questions. Here’s my take in answering them.

The person is really struggling. I know exactly what they are going to say. Shouldn’t I finish their sentence? They are trying so hard to get the words out.

It depends. Some people find it helpful when others finish their sentence, but many want to finish it themselves. This may mean having to wait a few seconds for them to say the word even though you know exactly what they are intending to say.

Stuttering is different from a word finding disfluency that we all often have. You may get stuck because you can’t quite put your finger on the word you want. We refer to this as a language block, as opposed to stuttering, which is a speech block. In the case of a language block, it is helpful to have someone finish your sentence. We’ve all had that “Yes, that word - thank you!” moment with others. This is NOT stuttering. A person who stutters knows exactly what he/she wants to say; it’s just physically stuck, like someone holding their hands to your throat making it impossible for you to get words out.

If you are not sure how to react when someone is in a block, just ask!

Should I maintain eye contact with the person while they are stuttering? I don’t want to make them uncomfortable.

It is polite to maintain eye contact with others as they speak, and there should be no exception for someone who stutters. One of the first skills we practice in therapy is eye contact because it helps increase confidence, decrease mind reading, and is a good communication strategy.

Many listeners break eye contact with the person who stutters for fear of making them uncomfortable. But breaking eye contact may send the vibe that you are uncomfortable with the stuttering.

But what if the person breaks eye contact with me?

People who stutter will often break eye contact when they are in a disfluency. In this case, it is up to you how you respond. I advise communication partners to maintain eye contact with the person who stutters, even if the person themselves breaks eye contact. This helps let the person who stutters know that when they are ready to practice eye contact, they have a supportive person who is listening to them and comfortable with their disfluencies.

I shouldn’t bring up the person’s stuttering. This might make it uncomfortable for them.

This is a tough one that depends heavily on the person. Some people, especially early on in therapy, are very resistant to talking openly about stuttering. Some people, however, do want to talk about it but are unsure of how and when to bring it up. Stuttering is often the elephant in the room that everyone notices, but no one knows how to address. If you have a burning question, ask it! Approach it in an inquisitive, curious way. But please don’t assume you have the cure to stuttering. The worst thing to say is, “I used to stutter as a child, but I overcame it” or “One of my friends stutters, but when she sings she doesn’t!” We realize that you are just trying to help, and be hopeful, but this only makes it harder for the person who stutters. If the person stutters into adulthood, they are likely not going to suddenly stop stuttering, so telling them stories about how you overcame stuttering by drinking goat’s milk is not helpful (yes this has happened to me).

I tell my child/significant other/friend that famous people like James Earl Jones overcame their stuttering and that they can too. This is encouraging to them right?

Ah, we love the message hard work pays off but sometimes, no matter how hard a person works on their “fluency techniques” they just won’t work. Celebrities that identify as people who stutter but don’t exhibit outward disfluencies are often discouraging to people who stutter. Celebrities like George Springer who openly stutter are much more influential.

Telling your child or significant other that they can do something because others did it can be detrimental if they’re never able to do it. We need role models that display imperfections, not ones that overcome their imperfections to become “normal.”

I heard that 80% of children outgrow their stuttering. Will my adult child/significant other/friend ever outgrow their stuttering?

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but likely not. Recovery rates are very high in early childhood, but steadily decrease with age. This means that a 3, 4, or even 7 year old is likely to recover from their stuttering, but a teenager or adult is past the “critical period” of stuttering recovery. However, just because they will probably not naturally recover from their stuttering, doesn’t mean they can’t “overcome” their stuttering. This requires interpreting “overcoming” in a different way. A person who stutters may “overcome” their stuttering by no longer avoiding words, saying all that they want to say, and participating in society without stuttering holding them back. Acceptance and desensitization towards stuttering often breeds fluency.

I know stuttering isn’t caused by anxiety or nervousness, but sometimes during an anxiety provoking situation (like a presentation or talking with a person of authority) my child/significant other/friend stutters so much more than when they’re talking to me! And sometimes, even within a conversation, the stuttering seems so variable. Why is this?

This one came to me at a wedding. I was having a pretty “fluent day” – talking to my boyfriend, catching up with old friends, and talking to my parents on the phone. Then, out of nowhere, the stuttering “monster” hit my throat right as I was saying congratulations to the bride and groom at brunch the next day. It was the longest block I have had in years. My boyfriend was in shock. After the conversation he laughed and asked, “What was that? You were REALLY nervous!”

I thought back to the moment. What really happened? Time pressure, talking to “authority”, lack of confidence, exhaustion, I don’t know, I’ll never know. But I stuttered a lot more than “average”, just like a person may sometimes be a little more tired than “average” or a little more depressed than “average”. I wish I could explain the science behind it, but until then, it just is.

Are there certain words that people who stutter always stutter on? I find that my child/significant other/friend always stutters on the word stutter!

Every person who stutters has his/her own unique “feared” words or sounds. There are theories that vowels and stops (like p and b) are harder because of the hard closure of the vocal chords, but there are as many feared sounds as there are people who stutter. Almost everyone has trouble with his/her name regardless of the sound it starts with. I’ve even heard of people changing their name to something “easier” to say and then they begin stuttering on that name!

There is research to suggest that children stutter more on function words and adults stutter more on content words, implying an association between grammatical structure and stuttering.

But back to the original question - yes, a lot of people who stutter do stutter on the word stutter. It could be the “st” sound itself that is difficult, or it could be the fact that the word ‘stutter’ has a lot of meaning attached to it. It could also be that one or two times your child/girlfriend/boyfriend/friend stuttered on the word stutter and now every time he/she goes to say the word, the body goes in full flight or fight mode and gets stuck.

My friend says that she is a person who stutters, but I rarely/if ever hear her stutter! I have more disfluencies than her! I think she’s just being over-dramatic.

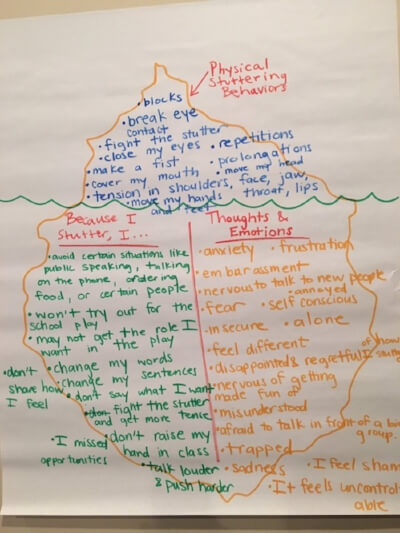

This is where the iceberg analogy of stuttering comes into play. Let’s take a look at a stuttering iceberg from some teens who stutter:

This is called a stuttering iceberg because, as we know from the Titanic, the part of the iceberg that was most detrimental to the boat was the part underneath the surface that the crew on the Titanic couldn’t see. The same goes for stuttering. Most of what is impactful about stuttering is not the tip (the outward disfluencies), but rather the bottom, or the thoughts and feelings and life impact associated with stuttering.

Look closely and you’ll see the fear, anxiety, shame, guilt, and missed opportunities.

For a covert person who stutters, their iceberg tip is tiny, but the “under the surface” features are massive. Their entire life is often dictated by their stutter. They may not go to parties, avoid making phone calls, change words for words they think they might stutter on, and the list goes on and on.

My child/significant other/friend stutters more when they are tired. Is this normal?

For some people, being tired/sick/stressed/etc. tends to be a trigger for stuttering. Note that this is different from being a cause of stuttering. The cause of stuttering is neurological and genetic, while triggers can be anything from anxiety to sleep deprivation. Think of asthma: the causes of asthma are physiological, but the triggers of asthma could include dust, fumes, pets, etc. These triggers are more likely to bring asthma out, but the person with asthma always has asthma even when they are not having an asthma attack.

Why do people tell me that they stutter? I can obviously see that they are stuttering. It seems like they are just stating the obvious.

Advertising, or self-disclosure of stuttering, is a significant part of therapy. Often times, people who stutter hide, avoid, and do whatever it takes to avoid being identified as a person who stutters. Disclosing helps lesson this fear, and helps the person begin to “take on the role” of a person who stutters. Additionally, disclosing helps clarify anything the listener might think is going on such as: is the person having a seizure? Did they forget their name? Are they nervous? Etc.

I become disfluent when I’m nervous or under time pressure. Does this mean I stutter?

It is common for people to have disfluencies when they are nervous, in high stress situations, or experiencing time pressure. You might hear fillers (ums, uhs, like), prolongations, or revisions. What you will not hear, however, is blocking. Blocks, or complete stoppages of sound, are a characteristic that differentiates stuttering from normal disfluencies. This produces a feeling of loss of control, which you will rarely see in a person who does not stutter.

Talking on the phone with people who stutter is weird. Sometimes I answer and just hear silence. How do I deal with this?

“Hello????? Hello?????? HEEEEELLLOOOOOOO?” I can still hear it like it was yesterday. During a previous part-time job working in a restaurant, I had to answer many phone calls. Time after time, I would block on the first word causing the person on the other end to engage in a cacophony of hellos.

If you are calling someone and you know they stutter, give them a couple extra seconds to answer. Make sure they are actually finished with their thought before responding. Be patient.

If you are answering the phone and there is silence or some light sounds on the other end, be patient – it may be a person who stutters.

What’s with all of this acceptance stuff? Stuttering just sounds BAD. I feel sad for people who stutter, shouldn’t they use techniques to try to be fluent and make it easier to talk?

This is a BIG question. Short answer – fluency techniques don’t always work. The techniques are your “fare-weather” friend, there for you in the good times, but never there when you need them. Acceptance isn’t “giving up.” It’s actually the opposite of that. It’s the first step. It’s accepting that stuttering, although not the whole of you, will likely always be a part of you. It’s a required step in order to take action. With admission comes acceptance and the willingness to change. Paradoxically, acceptance helps breed fluency. When you’re no longer trying to fight your stutter, your vocal mechanism is less likely to “freeze”. In addition to the physical impact, there is a significant positive psychological impact to acceptance. Giving oneself permission to stutter yields openness and confidence to take risks, say what you want to say, and no longer allow stuttering to hold you back.