When I tell people that speech IRL is a “speech therapy and inclusion consulting firm,” I get a lot of quizzical looks. As we spend more and more time working with companies, HR departments, heads of talent, and D&I (diversity and inclusion)/DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) committees, I’ve struggled to concisely articulate how we got here from speech therapy.

Thankfully, a new large-scale study on the merits of diversity training breaks it down. The name “speech IRL” is based on the principle that learning what to do is easy, but the real measure of change and progress is actually doing something “in real life”-- which is far more challenging.

The research conclusions Chang et al, in partnership with the Wharton School, echo almost word-for-word the founding principles of our practice.

In the researchers’ words, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America:

“The results suggest that the one-off diversity trainings that are commonplace in organizations are unlikely to be stand-alone solutions for promoting equality in the workplace, particularly given their limited efficacy among those groups whose behaviors policymakers are most eager to influence.” (1)

A more user-friendly summary by Jesse Singal from the British Psychological Society Research Digest describes the findings in layman’s terms:

“This outcome shouldn’t be too surprising: if you surveyed psychologists and asked them whether a single, 68-minute training could generate sizable behavioural effects weeks and months later, most would probably tell you no. Behaviour change is hard….That said [...] this study is laudable for showing exactly how diversity programmes should be evaluated: with an eye toward behavioural outcomes measured a significant period of time after the programme itself is delivered.” (2)

Behavior change specific to how human beings interact with one another?

Uh, yeah. That’s speech therapy.

Attitudes vs Behavior

In an extremely brief nutshell, this study measured how attitudinal training impacted both attitudes and behaviors. What do you believe, both consciously and unconsciously, and how do those beliefs influence your actions?

More specifically, if you want to change a person’s actions (say, to adopt more inclusive behaviors), what does that require?

The study explores some interesting nuances, but to echo Singal’s words, behavior change is indeed hard. Really, really, really hard. I say this as a professional who has spent years working with individuals who are extremely desirous of changing their communication behaviors (aka, speech therapy clients). Even when you are fully conscious of your values, your beliefs, your conscious and formerly-subconscious thoughts, and are intentionally committed, change is a helluva slog.

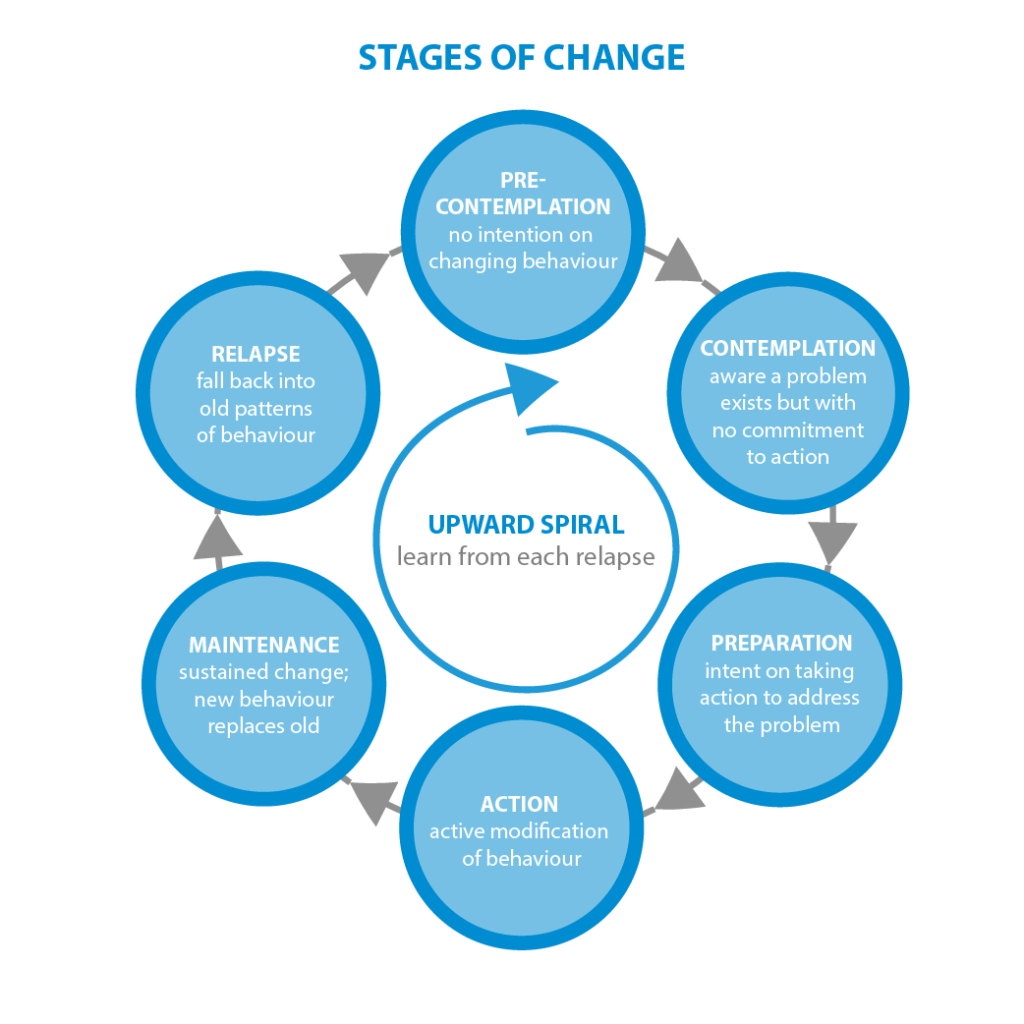

If you’ve ever tried to learn an instrument, lose weight, quit smoking, develop a meditation practice, or any kind of life-bettering activity, you’ve experienced this. You’ve gone through the stages of change (3): pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, and the oh-so-fun relapse.

To be sure, attitudes are an essential springboard for change. Change is uncomfortable and requires active cognitive persistence to maintain forward progress. If you don’t think the outcome is worth it, or are confused about why you’re putting yourself through this process, your efforts are likely to fizzle. This was demonstrated in the study: participants whose attitudes about diversity were more aligned with DEI initiatives exhibited more behavior change than participants who were newer or less mentally engaged with DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion, also sometimes abbreviated as D&I) concepts.

Building Towards Behavior Change

Both the study and the review acknowledge the importance of attitudes as a basis for change, while emphasizing that actual change is the real target of DEI trainings.

As the article mentions, there is not a well-established body of literature identifying what sort of DEI trainings are the most impactful and effective. Companies looking to hire trainers and consultants are often in the unenviable position of throwing a bunch of money at the wall and seeing what-- if anything-- sticks.

However, while diversity training science is still building a foundation, human behavioral change science has been chugging along nicely for some time. This is the foundation of how we approach communication change at speech IRL. We reverse-engineer abstract goals into discrete, sequenced, measurable behavioral objectives.

1. State the goal (or identify the problem)

“We want to be more inclusive.”

This is an abstract, undefined “being” goal. How will you know when you are “more inclusive”? What are the metrics associated with inclusivity? This is a crucial first step during our intake, to borrow from our therapisty lexicon. Only by understanding your measurable long-term objective can you start to build a meaningful plan.

This is where many curriculum-based diversity programs are at risk of falling short. Companies looking to change their culture are wildly diverse. Employees may cluster at various key points along the diversity attitudinal and behavioral spectra. One-size-fits-all leaves a lot of people feeling left out.

A proper diagnostic intake enables companies to understand their goals fully and clearly, define the specific attitudinal and behavioral targets, and set the scope for long-term learning and change.

2. Separate, then correlate

Most people (and companies) describe cultural or experiential goals with state- or being-based language. “We want to be more inclusive.” “We want our employees to feel safe.” Being is rather metaphysical, and feelings are not something a third party can dictate. An employer can't control how their employees feel. Of course, the actions and policies of a company can vastly influence how employees feel, which is why DEI is such a big issue.

States and emotions can be extrapolated from behavior patterns. What do employees who feel safe do? How do they behave differently than a workforce that does not feel safe? Are your employees behaving this way now? Why or why not? What policies, cultural norms, or other dynamics are in play? What specific changes would need to be implemented on the employer side to change these dynamics? What skills, freedoms, or structures need to provided to the employees?

State and being words are important. They reflect our instinctive, emotional processing of experiences. Words like safe, welcome, included, empowered, equal are powerful summaries of complex dynamics.

I like to use the analogy of constructing a brand new building. The goal or problem statement is the artistic rendering. It reflects tone, vision, inspiration. The architectural rendering brings this into sharper, more realistic form, at which point the engineering and structural needs become more evident. From there, it’s possible to create a blueprint, a complex skeletal framework with concrete details of every required sub-component.

3. Time and effort

Culture is like Rome. It is not built in a single training, or in an intensive marathon week of seminars. You can’t exercise your butt off for one week and consider yourself physically fit for the year. Crash diets are not sustainable, hence the name.

Actively, intentionally building or changing culture is a looooong process that is tedious and unglamorous. How do you begin construction on a new skyscraper? By digging a gigantic hole in the ground.

Everybody wants the quick fix. If you’re a professional looking to get rid of your stutter, feminize your voice, or conquer your lifelong speaking anxiety, there is an urgent desire for “just one or two quick tips.” Management teams are no different: we need to be more inclusive by next quarter! (Alas, money spent on inclusivity training does not directly correlate to actual inclusivity.)

Culture changes in steps, waves, and shifts. Each step is significant. If the majority of your workforce has never heard the term “implicit bias”, a short virtual training explaining the concept is a crucial foundational step for eventual behavior change! Knowledge cornerstones are essential-- but you can’t build the whole structure out of cornerstones.

At speech IRL, our favorite engagements are the ones that take a really long time. (And you might think, well of course, because those are the most lucrative!) Much like a music teacher or personal trainer, though, we actually spend a pretty limited amount of time with our clients, relative to the work that they are doing on their own. Our preferred format is a series of topically-progressed trainings that are spaced at least two weeks apart, with clear homework instructions and accountability mechanics for the interim. Processing time and practice are essential for learning (4).

Culture change doesn’t happen overnight. Learning and skills training must be appropriately “dosed” to maintain sustainable progress.

4. Measure, measure, measure

How do you know when you are “more inclusive”?

Measurement is only possible when you have clearly defined goals and concrete progress markers. Developing KPIs for culture change is the exact same process as for sales or revenue, and can even include numbers. DEI metrics should measure collective changes in behavior, both increases and decreases. Behavior is a proxy for understanding how we feel and think, so it’s critical that the measured behaviors correlate to the relevant high-level goals.

While the process for KPI setting is the same, DEI metrics are riddled with abstract, subjective nuance. When are behavioral outcomes appropriate, and when is self-report more accurate? How do you structure self-report data collection, including pre/post measurements? Are your metrics measuring what you really want to be measuring?

Clinical behavior specialists are masters of goal-setting. We have entire courses dedicated to marrying statistical methods with behavior change plans. Most of us continue to study goal-setting and goal-writing (two different skills) for our entire careers. Robust, useful goals account for context, graduated support level, change over time, responsible parties, and big-picture relevancy. With numbers.

Familiar frontiers

We recently held a share-out at our office, updating the therapy team on some recent consulting activities. Some of the newer clinicians had expressed an interest in understanding what exactly culture consulting has to do with speech therapy.

About halfway in, one clinician spoke up. “I have a question. I thought this was going to be different than what we do with our individual clients. But...this seems like the exact same thing, the exact same process. It’s therapy.”

That’s exactly what culture change is: therapy, on a collective scale. Changing culture, becoming more inclusive, is about changing how we view and interact with those around us. It’s changing how we communicate and the expectations around how we communicate. It’s understanding how our individual patterns contribute to a community dynamic. And then using that understanding to set concrete goals and make progressive changes.

Intentional, committed, long-term structured communication change? Yeah...that’s speech therapy.

References

(1) Chang, E. H., Milkman, K. L., Gromet, D. M., Rebele, R. W., Massey, C., Duckworth, A. L., Grant, A. M. (2019). The mixed effects of online diversity training. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(16) 7778-7783; DOI:10.1073/pnas.1816076116

(2) Singal, J. (2019). Finally Some Robust Research Into Whether “Diversity Training” Actually Works – Unfortunately It’s Not Very Promising. British Psychological Society Research Digest.

https://digest.bps.org.uk/2019/04/10/finally-some-research-into-whether-diversity-training-actually-works-unfortunately-its-not-very-promising/

(3) Norcross, J. C., Krebs, P. M. and Prochaska, J. O. (2011), Stages of change. J. Clin. Psychol., 67: 143-154. doi:10.1002/jclp.20758

(4) Agarwal, P. K., & Roediger, H. L. (2018). Lessons for learning: How cognitive psychology informs classroom practice. Phi Delta Kappan, 100(4), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721718815666