Your child is six, nine, twelve. Maybe he's been stuttering since he was two or three, or maybe you just started noticing it in third grade. Maybe she went through speech therapy in preschool, or maybe it seemed more prudent to "wait and see". Maybe the stutter went away, either on its own or apparently thanks to therapy. Maybe it's fluctuated, coming and going. Maybe it's always been there, regardless of what you've tried. Maybe your child got tired of going to therapy or it was just too hard to get to appointments, or it didn't seem to work.

Maybe, now, the stutter is worse. Maybe his teachers are commenting. Maybe she is getting teased by her peers. Maybe your mother is insistently asking when your child's speech will improve, and what are you doing about it. Maybe you feel embarrassed or anxious when meeting other parents, afraid they will notice that something is wrong with your child. Maybe you worry about the speaking demands of middle school, high school, college. Presentations, dating, job interviews. Maybe your child seems to care, maybe they don't. Maybe it still hasn't gone away.

Maybe you are thinking about speech therapy. Again, or for the first time. Will it help?

A Brief History of Speech Therapy

Traditional approaches to stuttering therapy throughout the twentieth century focused on physical speech mechanics. Therapy focused on having children and adults who stutter change their breathing patterns, control their speaking rate, and work towards fluent speech. This could be achieved with a combination of non-speech exercises (e.g. breath work and relaxation) and speech exercises (practicing word lists or reading aloud). The premise is that the stutterer's speech motor system is working incorrectly, and intensive physical practice was the key to "retraining" the system so that easy, fluent speech could be achieved.

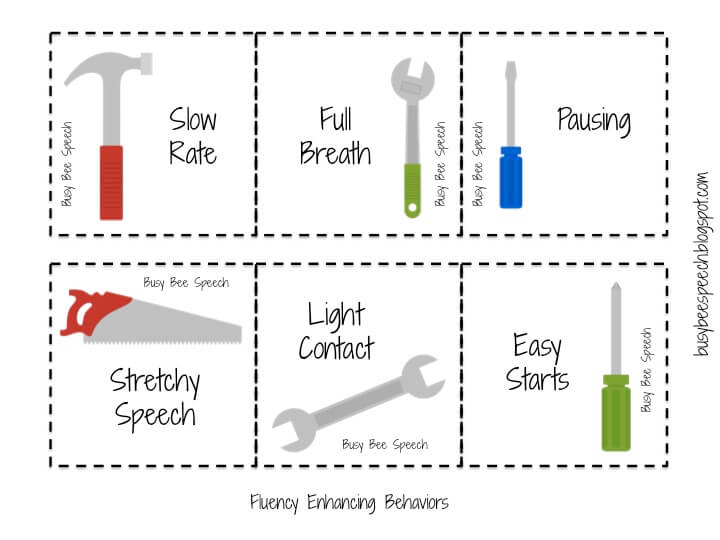

Many, if not all, speech pathologists still use these traditional techniques when treating stuttering. We have terms for different "speech tools": easy onsets, cancellations, pull-outs, linking, and more. These tools sometimes facilitate more fluent speech, or sometimes they just make talking a little easier, even if it is not perfectly smooth.

If you take your child to speech therapy, they will undoubtedly learn some of these classic techniques or tools to make talking easier. These tools are a fairly bread-and-butter component of modern stuttering therapy.

There has, however, been a shift in the past few decades in how many speech-language pathologists approach stuttering treatment. While your child may learn some tools, the SLP may tell you quite plainly that speech fluency is not the goal of stuttering therapy. Okay, so why am I paying you?

"Acceptance"

For many modern-day stuttering specialists, acceptance of stuttering is a primary goal of therapy, with speech mechanics being secondary (or possibly tertiary). Essentially, this means "being okay with the fact that you stutter." Acceptance-based speech therapy typically involves a lot of counseling, discussion, and education about stuttering (plus the traditional physical techniques). For kids, the goal is to build a child's self-esteem, self-identity, and confidence so that they can be a confident and comfortable communicator even if their speech is sometimes disfluent.

"Acceptance" is a pretty big concept that is a subject for another post (or book). It does not mean giving up or resignation, "You're always going to stutter, just deal with it." Acceptance means finding realistic, achievable goals that will allow you to accomplish what you want in life, and actively working towards those.

"Use your tools!"

Stuttering tools, by Lauren at BusyBeeSpeech.blogspot.com

Whether or not they've been introduced to the notion of acceptance-based therapy for stuttering before, most parents say they are pretty open to it. "I want my child to be confident when s/he's talking," say 100% of parents who bring their child to therapy. Great! We are all working towards the same thing.

A few weeks into therapy, the child's fluency has usually increased. When I check in with parents about their child's progress, they say, "Great! I've noticed him using his tools, and he's not stuttering as much. The teachers at school say they've noticed a big difference and that he's more fluent in class. What can I be doing at home to make sure he's using his tools more?"

This is the catch.

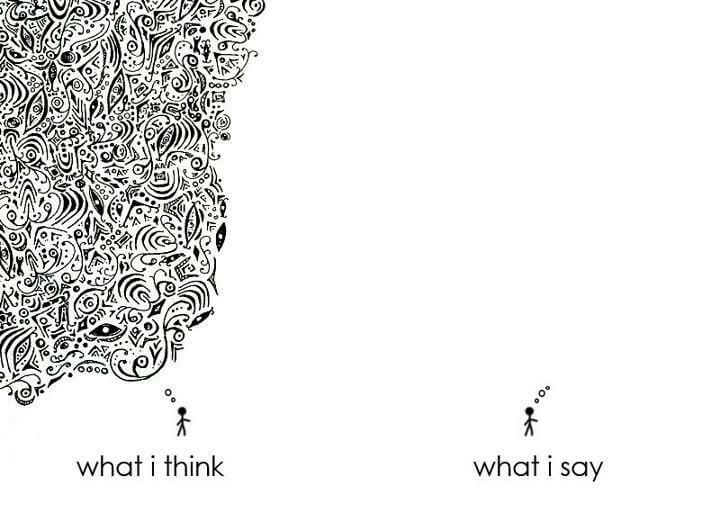

Cognitive load

Even for people who have been in therapy for many years, and have actively and intensely practiced tools, it usually requires some amount of mental effort and concentration to apply them in conversation. This is exponentially true if it's a challenging communication situation (competing to speak, feeling nervous, excited, etc.). It takes work; it is mentally and even physically exhausting. Try spending even 30 consecutive minutes concentrating intensely on your rate of speech while you're at work. How do you feel?

A lot of times, kids who stutter come home from a day of school and extracurriculars, and they have chores and homework. They are tired. They've completed all their responsibilities, "do this" "do that" "don't forget" for the day, and they may just want to talk. Freely, without thinking, without concentrating on their speech motor patterns.

She's really excited to tell you about how her art presentation went. She's not thinking about her blocks or using easy onsets. She's stuttering. You see her get stuck on a word.

"Try a cancellation," you suggest, reminding her that she has ways of handling these times.

She stops, concentrates, then smoothes out of her stutter and moves on to telling you. After she's done with her story, you ask some questions, then leave to fix dinner. "Nice job using your speech tools," you comment at the end, giving positive reinforcement to her speech efforts.

Translation

Children want their parents' approval (even though they don't always act like it!). This is very much true for speech. I've had family conversations where I know the 9-year-old hates therapy but he agrees to come because he can see how badly his mom wants him to "get better".

Unfortunately, coming from a parent, tool-based fluency reinforcement comments often have a very, very different impact than intended.

"Use a cancellation/pull-out/easy onset/tool" = Do this thing because you are supposed to do it.

"Nice job using your tools" = I like you better when you speak fluently.

The first time I heard these "translations" from another stuttering specialist, I was blown away by the weight of these words. I asked one of my close friends, a young woman who stutters, what she thought about this.

"Omygosh, YES. That's exactly what it means," she exclaimed.

Nothing is tool-proof

As adults, it is tough to hear kids stutter. Especially if it is our kid. At best, it makes them different. At the worst, it means there is something wrong with them, they have a problem. Maybe it even feels like your fault. Every repetition, funny facial tick, or silent struggling pause is a reminder of this. This can be magnified thousandfold when you watch their friends dominate a conversation, because your child can't get a word out, or when they come home and tell you that another kid on the playground is copying their speech.

The fact is, even if your school-aged child is a cancellation savant, he is likely going to be dealing with some degree of stuttering interference for the rest of his life. Tools may ease the block, but they won't ease the pain of the funny look from the cashier. Knowing you can use an easy onset doesn't eradicate the apprehension of having to introduce yourself in front of the class. And, sometimes, people try to use tools and they just don't work. And trust me, they have tried their very, very utmost best. Does that mean they are a lazy, incompetent, a failure?

The most important thing

Speech and voice are intimately and intricately connected to our identity (both Katherine Preston and NPR have written some great articles on this topic). As speech therapists, we talk about the importance of stuttering acceptance, because what it really is is self-acceptance. It is about accepting your imperfections, loving yourself, and living beyond the struggles. As a parent, accepting your child's imperfect speech means that you are accepting them. The reverse is also true: focusing only on speech "errors" is a constant reminder that they are not good enough. The time to work is in therapy, and your speech pathologist may also suggest setting time aside at home for specific practice time. Outside of that, though, let him speak freely. Let him be himself.

An at-home how-to guide

How do you show your child that you accept them and their speech?

Openly acknowledge stuttering. Acceptance does not mean pretending it's not there (that's "denial"). For younger kids who are less self-aware, non-judgmental acknowledging comments might be something like, "That was a tricky word!" (Make sure you always wait for your child to finish speaking before saying something!) For older kids who are highly aware of their speech, you can ask them generally about their thoughts and feelings. "How are you feeling about your speech?" If you ask a question like, "How was your speech?" and get a response that says, "Bad," ask what they mean (were they very disfluent? did someone laugh at them?), then ask specifically how it makes them feel.

Don't hyperfocus on stuttering. While some children do experience teasing and bullying, most kids who stutter have pretty accepting friend groups and teachers, and so don't feel concerned about the fact that they stutter. If your child seems nonchalant about his speech, don't harp on it. Respect his communication choices, even if that means not using the tools he's learned in therapy.

Encourage them to take risks. School play? Science fair presentation? Debate team? Communication is about so much more than fluency, and kids who stutter can excel at all these activities. While you may want to protect her from what seems like a potentially embarrassing or difficult experience, you will set her up for far greater success in the long term if you teach her to challenge herself and go outside her comfort zone.

Be present. Stuttering, in my opinion, is often scarier for parents than for kids. Many kids who stutter are well-adjusted to their speech, have friends, and do fine in school. Their parents, meanwhile, are fretting about college presentations, job interviews and finding a spouse. All of those things can be managed when the time comes. For now, be present with your child and where s/he is in their life, right now, resisting the urge to worry into the future. If things are going well, celebrate that. If things are tough, show them that you are there to walk alongside them.

Find support for yourself. Childhood stuttering is often far more complex for parents than for the child themselves. You are not the only parent(s) going through this. Local and online support groups for stuttering exist, and allow you to build relationships with others who have dealt with and are dealing with this. Both the National Stuttering Association and FRIENDS have wonderful family support options. You can also ask your speech pathologist for local support suggestions.

Talk to your child's speech-language pathologist. Parents, you are critical to your child's therapy process. Your child may not always get sent home with practice sheets, but that does not mean there is nothing to be done at home. You know your child better than we do, and you will be the one supporting them long-term. Stuttering affects the whole family, and so we want to support your whole family. That means you.

Accept yourself. Stuttering is not your child's fault, and it is not your fault. Past theories and myths about stuttering have often placed blame on parenting methods and behaviors. Modern studies and scientific research tell us this is not the case. Second-guessing past actions (putting your child in therapy earlier, or in better therapy, or in more intensive therapy), is likewise no guarantee. Your child's stuttering is not a sign that you are a negligent, overbearing, or bad parent. It is, however, an opportunity for you to be a supporting, caring, understanding parent.

You can do it.